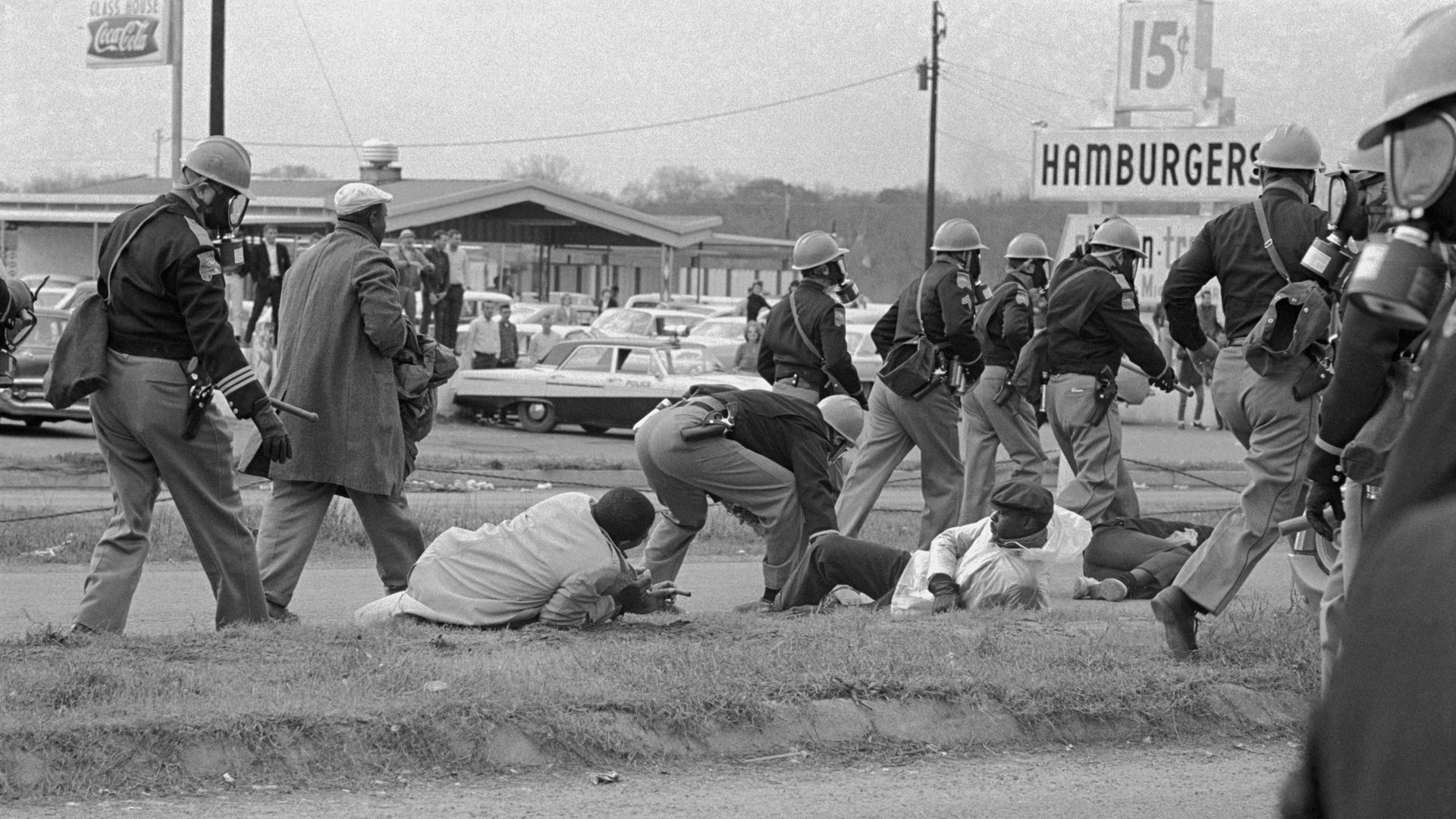

Charging Alabama state troopers pass by fallen demonstrators in Selma on 7 March 1965. The civil rights movement in the U.S. is credited as advancing photo journalism.

BY:

Eric De Grasse

Chief Technology Officer

Project Counsel Media

1 June 2020 (Paris, France) – The ways Americans capture and share records of racist violence and police misconduct keep changing, but the pain of the underlying injustices they chronicle remains a stubborn constant. As my colleague, Caterina Conti, noted over the weekend, there is more to be said about the burgeoning genre of videos capturing the deaths of black Americans, and the complex combination of revulsion and compulsion that accompanies their viewing. They are the macabre documentary of current events, but the question remains about whether they do more to humanize or to objectify the unwilling figures at the center of their narratives. Death is too intimate a phenomenon to not be distorted by a mass audience. Very few of us knew who George Floyd was, what he cared about, how he lived his life. Today, we know him no better save for the grim way in which that life met its end.

Given its complexity, just a few points:

Driving the news: After George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked wide protests, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz said, “Thank God a young person had a camera to video it.”

Why it matters: From news photography to TV broadcasts to camcorders to smartphones, improvements in the technology of witness over the past century mean we’re more instantly and viscerally aware of each new injustice.

• But unless our growing power to collect and distribute evidence of injustice can drive actual social change, the awareness these technologies provide just ends up fueling frustration and despair.

For decades, still news photography was the primary channel through which the public became aware of incidents of racial injustice.

• A horrific 1930 photo of the lynching of J. Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith, two black men in Marion, Indiana, brought the incident to national attention and inspired the song “Strange Fruit.” But the killers were never brought to justice.

• Photos of the mutilated body of Emmett Till catalyzed a nationwide reaction to his 1955 lynching in Mississippi.

In the 1960s, television news footage brought scenes of police turning dogs and water cannons on peaceful civil rights protesters in Birmingham and Selma, Alabama into viewers’ living rooms.

• The TV coverage was moving in both senses of the word.

In 1991, a camcorder tape shot by a Los Angeles plumber named George Holliday captured images of cops brutally beating Rodney King.

• In the pre-internet era, it was only after the King tape was broadcast on TV that Americans could see it for themselves.

Over the past decade, smartphones have enabled witnesses and protesters to capture and distribute photos and videos of injustice quickly — sometimes, as it’s happening.

• This power helped catalyze the Black Lives Matter movement beginning in 2013 and has played a growing role in broader public awareness of police brutality.

Between the lines: For a brief moment mid-decade, some hoped that the combination of a public well-supplied with video recording devices and requirements that police wear bodycams would introduce a new level of accountability to law enforcement.

• But that hasn’t seemed to happen, and the list of incidents just grows.

• Awareness of the problem increases, but not accountability for police actions.

The bottom line: Smartphones and social media deliver direct accounts of grief- and rage-inducing stories.

• But they can’t provide any context or larger sense of how many other incidents aren’t being reported.

• And they don’t offer any guidance for how to channel the anger these reports stoke — or how to stop the next incident from happening.

And I know we are witnessing a bigger picture here if we just stand back a little. The social upheaval of the 1960s has finally met the political polarization and institutional dysfunction of the present.

And THAT is the story of American political polarization. For a time, in the 20th century, our political coalitions did not echo our social divisions, our parties were mixed enough to see little benefit in sharpening the contradictions, and so the political system often calmed our conflicts. It did so imperfectly, and often unjustly, but America held together when it could have come apart easily.

Today, our political coalitions are our social divisions, and that changes everything. When there is a rift within a party, the incentive is to bridge it, or ignore it, to maintain cohesion and retain wavering voters. When the rift is between the parties, the incentive is to escalate, to sharpen differences and mobilize supporters. As my partner, Greg Bufithis, put it:

The technological and financial understructure of politics and media transformed in ways that reinforced the polarization of the parties, as nightly newscasts and daily newspapers gave way to the quivering nervous system of Twitter, the identitarian incentives of Facebook, the shouting on cable news. These institutions are in feedback loops with each other, and what is fed back and forth, growing louder and louder, is conflict, collision, and fury. Trump is that system summoned into human form, a social media savant and cable news favorite who rode the feedback loop of outrage into the White House. He understood our divisions better than we did, and that is seen, in our age, as a form of political genius.

And what makes Trump successful is what makes him dangerous: he knows only the one thing, and knows it too well. All he can see is division; all he knows is discord; all he can do is escalate. He is the King Midas of strife, turning the country he leads into the thing he believes we are, the thing he himself is.

I see no escape for America. The forces unleashed by Trump will not go away with his demise.

• Worthy of your time: An N.Y. Times video recreation, “8 Minutes and 46 Seconds: How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody”