One of the biggest threats to 21st century international peace is invisible

23 September 2020 (New York, NY) – World leaders gathered virtually yesterday for this week’s United Nations General Assembly, with the UN’s historic 75th anniversary overshadowed by strongmen leaders, fraying relations and a sense of intensifying international crisis. The summit was forced online this year due to the pandemic and the 14-day quarantine regulations in New York City.

COVID-19 loomed heavily over the first day of the event. Instead of meeting in person, UN officials, presidents and prime ministers sent pre-recorded speeches to mark the occasion. Press passes to cover the event from on-site press rooms were very easy to get this year, probably due to the virtual nature of the event as we all participated in “The Mother of All Zoom Calls”.

NOTE: getting here from Europe was “unusual”. Despite all the chatter about COVID-19 restrictions and close monitoring, I was not “COVID-checked”, neither at my European point of departure nor at my U.S. point of arrival, although I am still in quarantine for a few more days (I arrived earlier anticipating this). I shall keep the departure/arrival cities under wraps for now since I may need to return to Europe via the same route.

I decided to attend but not for the politics. The Tuesday main sessions (again) highlighted the complete lack of unity between UN members, the tensions particularly apparent between the U.S. and China, numerous references to the health crisis as “our own 1945 moment” (multiple references to World War II in everybody’s speech), plus a liberal peppering of COVID-19 as “a toxic virus shaking the democratic underpinnings in many countries.”

No, I came for the sessions on cyber security and cyber war. Those sessions are virtual, too, but many of the participants are based in NYC and D.C. (my two stops on this U.S. trip) and I wrangled some meet-ups with participants and my own cyber security contacts after those sessions. To prepare, I have done a fair amount of reading and been in about 4 “pre-UN event” Zoom chats, so the following are a few notes with links to articles you might find of interest for further reading.

We all certainly know that the biggest threats to 21st century international peace is invisible. It recognizes no borders and knows no rules. It can penetrate everything from the secrets of your government to the settings of your appliances. This is, of course, the threat of cyberattacks and cyberwarfare.

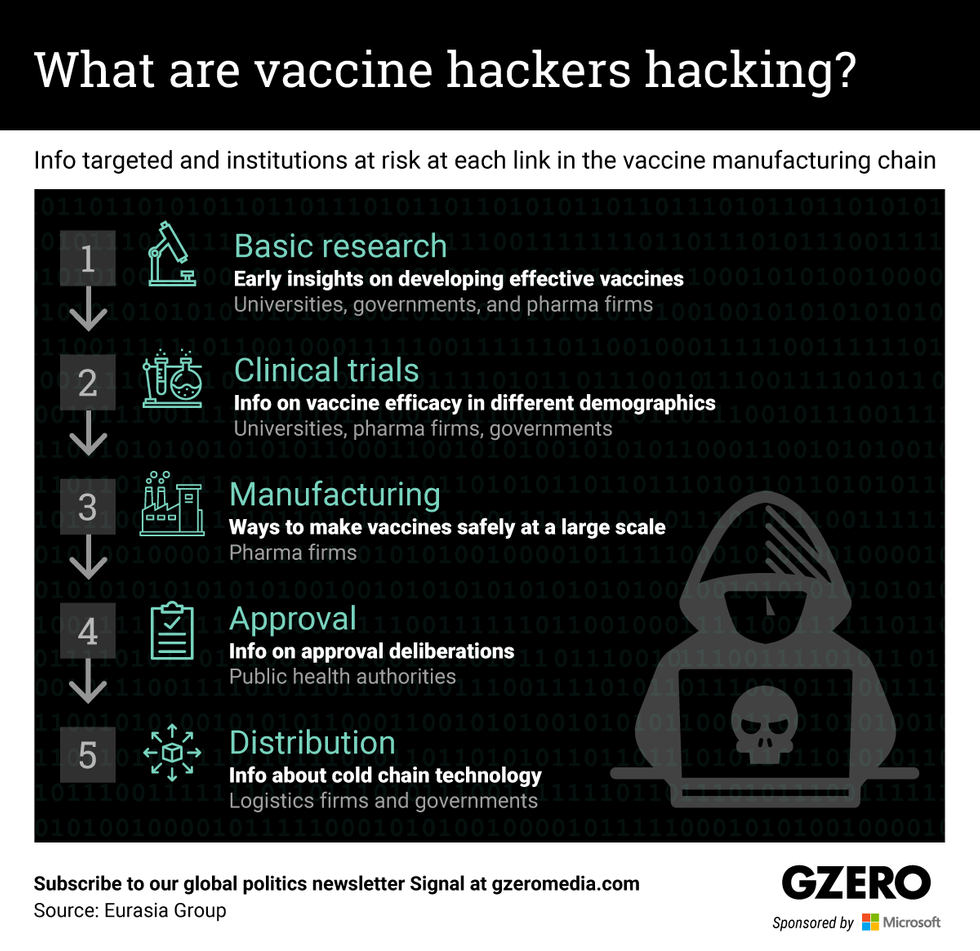

During the coronavirus pandemic, cyberattacks have surged, according to watchdogs. This isn’t just Zoom-bombing or scams. It’s also a wave of schemes, likely by national intelligence agencies, meant to steal information about the development and production of vaccines. Attacks on the World Health Organization soared five fold early in the pandemic. One interesting slide from a GZERO Zoom chat last week:

So, obvious question: why is the threat of cyberwarfare growing, and why isn’t more being done to stop it? Well, hacking is increasingly the business of nation-states. Not so long ago, hackers were mainly hooded freelancers sitting in their basements stealing credit card numbers. Now they are increasingly the employees of national intelligence services. And why are countries investing more and more in the cyber game? Well simple. For one thing, hacking is a cheap way to level the playing field with larger global rivals. For North Korea or Iran, you no longer need a powerful military in order to project power across the globe. You just need a laptop and a few good programmers. What’s more, unlike missile launches or invasions, the targets can’t always tell where a cyberattack has come from. Plausible deniability comes in handy, especially when attacking someone bigger than you.

And as I have noted in previous posts, targets are getting fatter. As countries build out 5G networks, data flows will increase massively, as more than a billion more people move online over the next decade. The so-called “internet of things,” the network in which everything from your watch to your (potentially self-driving) car to your refrigerator are being hooked up to the internet. That said, huge gaps in internet access persist. An excellent piece distributed by GZERO for its Zoom chat last week can be accessed here.

And there are no rules. Conventional war has rules about whom you can and cannot attack, occupy, or imprison. They aren’t always respected or enforced – but the cyber realm has very few rules, mainly because the world’s major cyber powers don’t want them. If you’re Vladimir Putin, hacking has brought dividends that your flagging economy and mediocre military cannot. If you’re the US, you’re historically wary of any binding rules about the conduct of war. So, while various groups of countries have, under UN auspices, started to develop “norms” – they are not binding. But at a session this morning, one speaker noted “unfortunately, it may take a catastrophe to create those rules”. So far, the damage inflicted by hackers has mostly been economic. In 2017, the NotPetya virus, which targeted Ukraine, quickly spread around the globe, inflicting $10 billion worth of pain. It was, so far, the worst cyberattack in history.

But it’s not hard to imagine a cyberattack on a hospital network, a power grid, or a dam that kills thousands of people and forces even more from their homes. In fact, at this morning’s session a presenter showed exactly how that will happen. Not “could happen”. Will happen. And so how can those responsible be called to account? One item we discussed this morning was the “improvement” in cybercrime technology which makes attribution harder. The tools look more like those of nation-states. And given Russia outsources lots of its cyber attack work to criminal cyber gangs, from an attribution standpoint it’s very difficult to determine if an actor is working at the behest of a foreign government … or if they’re doing criminal activity on their own time.

And what would it take to make future such attacks much less likely? Will it take an event that inflicts that much human damage for governments and tech companies to sit down and hammer out cyber-rules of the road? I’ll have more next week after the UN sessions are over.

Cybersecurity: a booming business and the UK stakes a claim

The United Kingdom has seen record growth for cyber security startups. The record growth in the cybersecurity field is due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the heavy demand on Internet and digital services. Internet and digital services must be protected from potential bad actors stealing individuals’ information or be mischievous during Zoom meetings … or more serious nation-state attacks. Tech Round explains more about UK cybersecurity growth in “Cybersecurity: The Fastest Growing UK Startup Sector During COVID-19.”

Before the pandemic struck, cybersecurity focused on financial and regulatory risks. Cyber risk management is now a hot ticket for investors. COVID-19 also points to a future where more people will be working remotely, organizations will host their data offsite, and more services will be online. From the article:

Historically IT security has represented only 5% of a company’s IT budget but due to remote working and transition to online or cloud-based solutions, cybersecurity has been thrust to the centre of business continuity plans, having proved its worth in enabling business objectives during lockdown. Not only will every company see the benefit of having this expertise in-house, but they will be looking externally for tools, services and advisors to help guarantee the future-proofing of their business by way of solid and robust cybersecurity provisions.

What is even more interesting as I dug into this are the venture capitalists behind the investing. The PHA Group breaks down who the “5 Key VCs Backing Cybersecurity Startups” are. According to the LORCA Report 2020, a half billion pounds were fundraised in the first half of 2020 for cybersecurity startups. This is a 940% increase compared to 2019. Venture capitalists also want to invest their money in newer technologies, such as AI, encryption, secure containers, and cloud security. The five companies that invested the most in UK cybersecurity are Ten Eleven Ventures, Energy Impact Partners, Index Ventures, and Crosslink Capital – many of whom I have met due to their appearance as a speaker or attendee at the mega International Cyber Security Forum in Lille, France.

More to come.